PQCs Unsung Hero - Zero Knowledge Proof Algorithms

During the Helion years of early EMV I became familiar with ZKPs and in particular GQ2. I was honored to host Louis Guillou in Omaha and discuss how GQ2 could revolutionize EMV having very fast yet secure operations that would be much easier to implement on the limited compute capability of smartcards at that time. Also the cost of the chip would be significantly less expensive.

Here is a link to his work at France Telecom and more broadly with luminaries in the crypto world: https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/Louis-C-Guillou-69714734

Regrettably for ZKPs, at the time First Data had another path it was taking called Account Authority Digital Signature that favored ECC (which had great merit). It would have used an ECC enabled smartcard to digitally sign each transaction, as well as terminals and core switches along the chain of custody up to the final transaction verification in our Mainframes. Lynn Wheeler and his wife were the co-inventors of this approach which sadly was not brought to fruition. So GQ2 never caught traction at First Data. I will post in coming days links to Lynn's website, a great thinker I was incredibly blessed to be exposed to.

As background for GQ:

The GQ (Guillou-Quisquater) zero-knowledge protocol was invented by Louis C. Guillou and Jean-Jacques Quisquater. They introduced the scheme, which is used for identification and digital signatures, in a paper presented at the 1988 CRYPTO conference. The GQ protocol is based on the difficulty of inverting the RSA cryptosystem without the private key. It was developed as a more efficient alternative to earlier zero-knowledge proof systems, taking inspiration from the work of Amos Fiat and Adi Shamir. The fundamental concept of zero-knowledge proofs, which is the broader family of algorithms that GQ belongs to, was first introduced by Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio Micali, and Charles Rackoff in 1985.

ZKP has evolved since then to be even more efficient, smaller key sizes, faster execution. The one most commonly referenced is MQOM. It is a tool in the toolbelt that is often overlooked. I thought it would be of great use to compare lattice PQC algorithms vs ZKP and where each shines in particular.

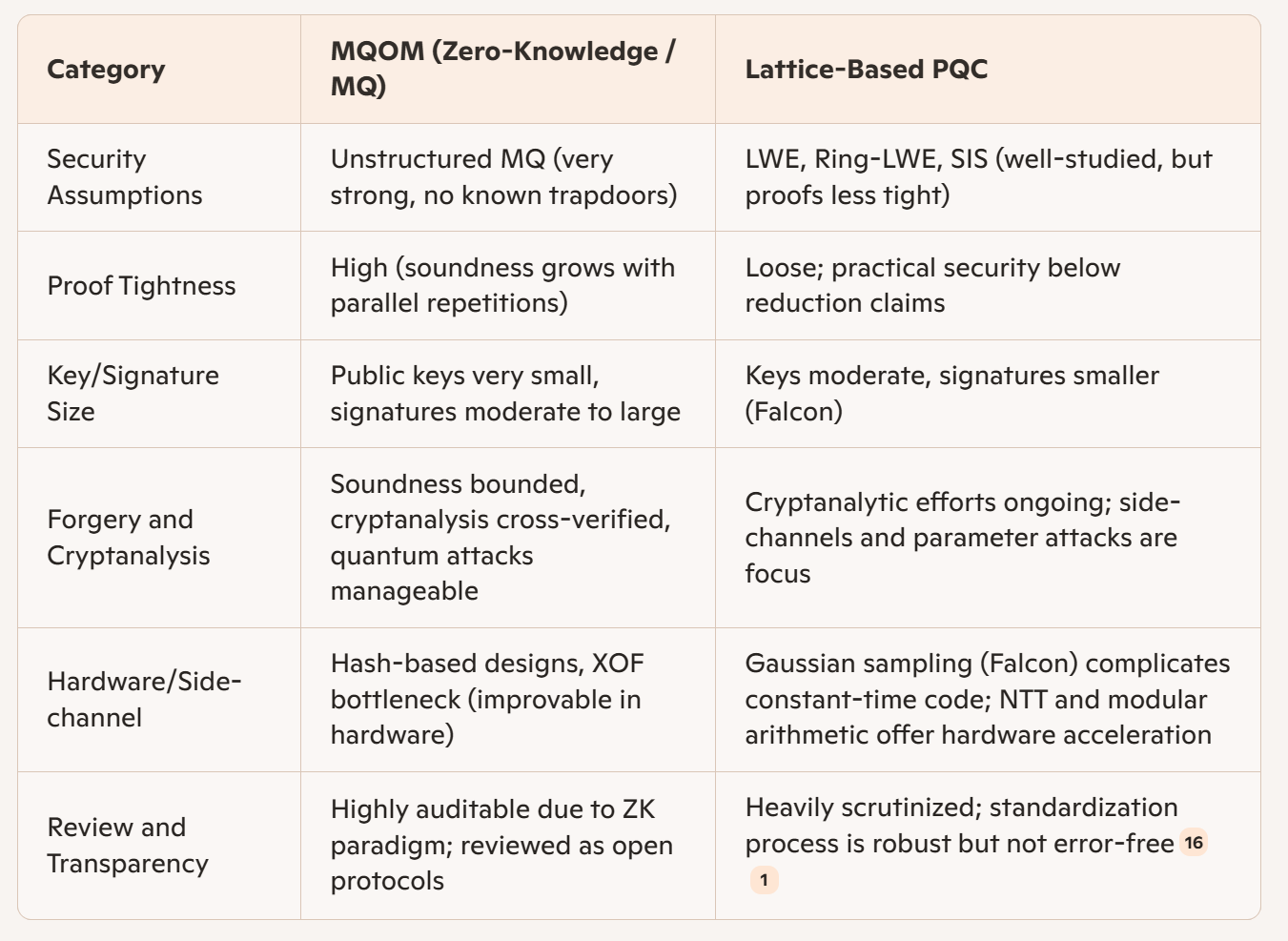

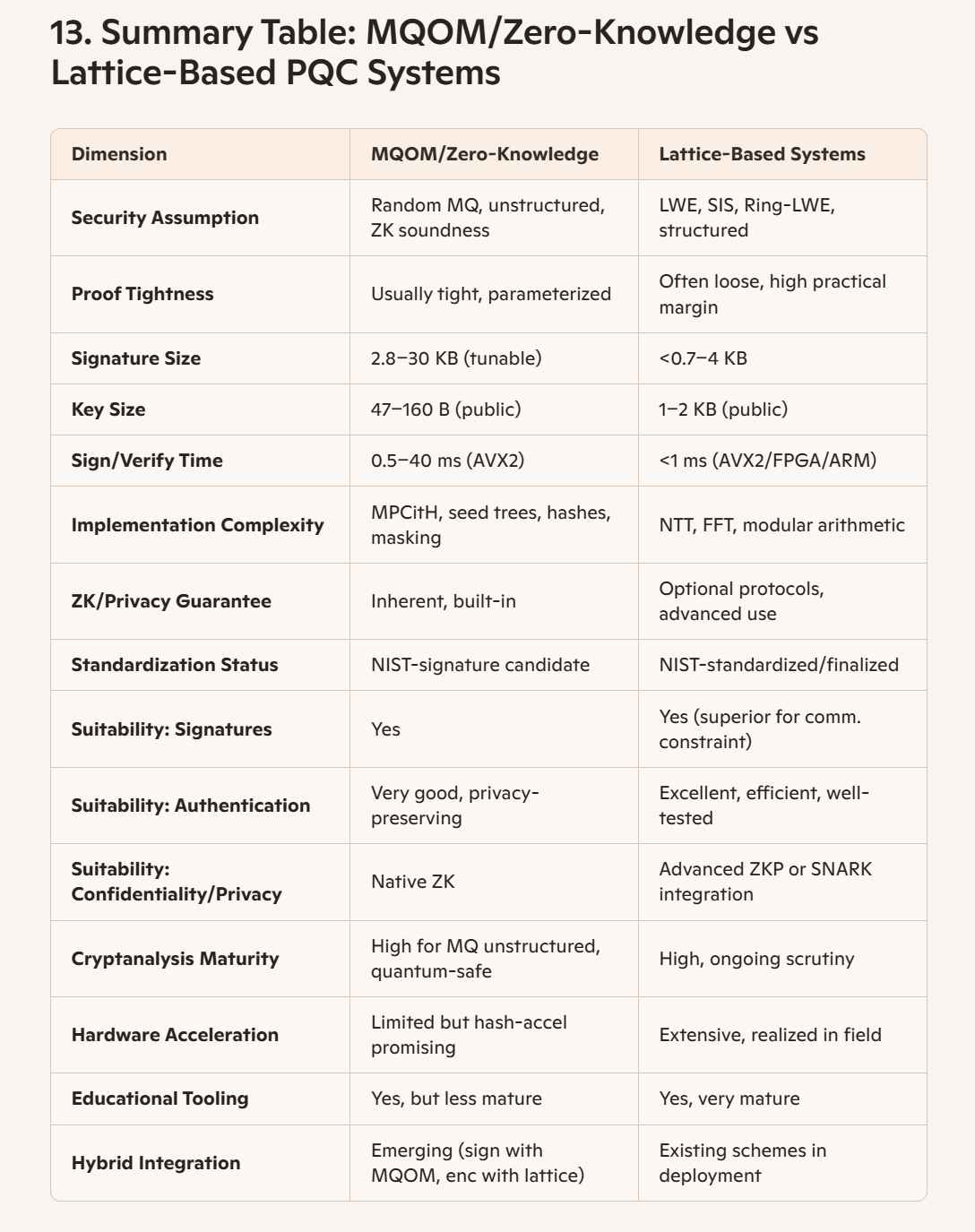

Comparison of MQOM and Zero-Knowledge vs Lattice-Based Post-Quantum Cryptography:

Comparing MQOM/Zero-Knowledge and Lattice-Based Post-Quantum Cryptography: Security, Performance, and Application Suitability

Introduction

The impending rise of quantum computers presents a fundamental threat to widely used cryptographic schemes, particularly those based on factorization or discrete logarithms. In anticipation of this paradigm shift, post-quantum cryptography (PQC) seeks algorithms resistant to both classical and quantum adversaries. Two prominent and fundamentally different families of PQC candidates stand out: Multivariate Quadratic (MQ) and zero-knowledge proof (ZKP)-based systems (with MQOM—Multivariate Quadratic On My Mind—as a leading example), and lattice-based systems (notably, those based on the Learning With Errors problem, such as NIST-standardized CRYSTALS-Dilithium and Falcon).

This report provides a comprehensive, technical, and application-oriented comparison between MQOM/zero-knowledge proof-based PQC approaches and lattice-based cryptography. We focus on their respective security assumptions, implementation and performance characteristics, cryptanalysis, key/signature sizes, cryptographic primitives, standardization status, and suitability for major uses such as digital signatures, authentication, and privacy-preserving protocols. Special attention is dedicated to concrete benchmarks, cryptanalytic results, and the nuances of adoption in settings ranging from cloud systems to embedded devices and blockchain platforms.

1. Foundations

1.1 Multivariate Quadratic and MQOM Overview

MQOM (Multivariate Quadratic On My Mind) is a digital signature scheme whose security rests on the hardness of solving random systems of quadratic equations over finite fields—commonly known as the MQ problem. The MQ problem is NP-complete, and its unstructured, randomly instanced form is considered among the most conservative and time-tested foundations for post-quantum cryptography2. MQOM leverages advanced techniques from the zero-knowledge proof realm, specifically the MPC-in-the-Head (MPCitH) paradigm, allowing it to construct signatures as non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs of possession of a solution to the given MQ instance1.

The MQOM framework has two primary variants: the sigma variant (-r3) and the five-round variant (-r5), with tradeoffs between signature size and generation speed. MQOM also supports parameter tuning, enabling adaptation to various security levels (NIST Levels 1, 3, and 5) and performance footprints. Public keys are compact (e.g., 52–160 bytes), allowing for low communication overhead, while signature sizes, though larger than lattice-based competitors, are optimized to the lower end of MPC-ZK signature schemes (2.8–4.1 KB for 128-bit security).

1.2 Lattice-Based Cryptography Overview

Lattice-based cryptography is underpinned by the presumed quantum-hardness of problems such as Short Integer Solution (SIS), Learning With Errors (LWE), and their variants. Unlike classical problems, no efficient quantum algorithms are known that can solve these intractable lattice problems with practical parameters6. Lattice-based schemes are the backbone of modern PQC standardization, with high-profile algorithms such as CRYSTALS-Kyber (for encryption/KEM) and CRYSTALS-Dilithium and Falcon (for signatures) being recently standardized by NIST (FIPS 203, 204)8.

Lattice-based signatures, historically encumbered by implementation complexities (notably Gaussian sampling), have progressed rapidly. State-of-the-art schemes achieve competitive speed, moderate to low signature size, and robust implementations across hardware modalities10.

1.3 Zero-Knowledge Proof-Based PQC Solutions

Zero-knowledge proof systems, such as zk-SNARKs, zk-STARKs, and their post-quantum variants, are central in privacy-preserving cryptography and underpin several PQ signature schemes (e.g., Picnic, Banquet, and MQOM). MPCitH-based protocols allow for non-interactive, zero-knowledge proofs based on hash functions (quantum-safe), while certain advanced ZKPs employ lattice assumptions for efficient, log-sized proofs12. Zero-knowledge functionality is now being explored both as a cryptographic primitive and as a tool within advanced constructions such as ring signatures, confidential transactions, and privacy-centric blockchains.

2. Security Assumptions and Cryptanalysis

2.1 Security Assumptions

2.1.1 MQOM and Multivariate Quadratic

- MQOM’s security derives from the hardness of the MQ problem: Given a randomly sampled system of m quadratic equations in n unknowns over a finite field, recover a solution x. No subexponential quantum or classical attacks are known for randomly instanced MQ problems with sufficient parameters2.

- Conservative hardness: The lack of trapdoor structures (as in unstructured MQ schemes like MQOM) avoids structural vulnerabilities that have affected earlier multivariate schemes (e.g., Rainbow, for which parameter overclaiming was a problem)2.

2.1.2 Lattice-Based Assumptions

- Lattice cryptography is built on LWE, Ring-LWE, Module-LWE, SIS, and NTRU. These problems are worst-case to average-case hard and are currently resilient to all known quantum algorithms6.

- Security reductions: While theoretical reductions exist, practical security is often much less than implied by proof tightness. There are notable tightness gaps; e.g., Regev’s worst-case to average-case reduction for LWE presents a 2^504 gap for NTRU dimensions5.

- Attack landscape: While lattice attacks have evolved (BKZ lattice reduction, combinatorial attacks, side channels), parameter choices in standardized schemes remain robust, and continued cryptanalytic effort is active.

2.1.3 Zero-Knowledge Proof-based Variants

- Hash-based and MQOM zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) are quantum-safe by construction. For lattice-based ZKPs (e.g., LaZer library, Lantern), security is as strong as the underlying lattice assumptions17.

- zk-SNARKs (elliptic curve pairings) are not quantum-safe, while zk-STARKs (hash-based) are, but with larger proof size and higher computational cost11.

2.1.4 Cryptanalysis

- MQOM: Security estimates are cross-verified using the MQ estimator, incorporating classical and quantum algorithms: HybridF5, FXL, Crossbred, each with complexity estimates into the hundreds of bits (well above 2^128 for NIST Cat I). Quantum algorithms for MQ show only sub-quadratic improvements, so parameters suffice for post-quantum claims2.

- Lattice-Based: Cryptanalysis includes lattice reduction, dual attacks, quantum speedups (e.g., quantum sieving), and side-channel analysis. Proofs are not tight, but standardized parameters are set with conservative safety margins; Falcon’s floating-point arithmetic, for example, presents constant-time implementation issues on certain microcontrollers10.

3. Performance Benchmarks

3.1 MQOM & Zero-Knowledge Systems

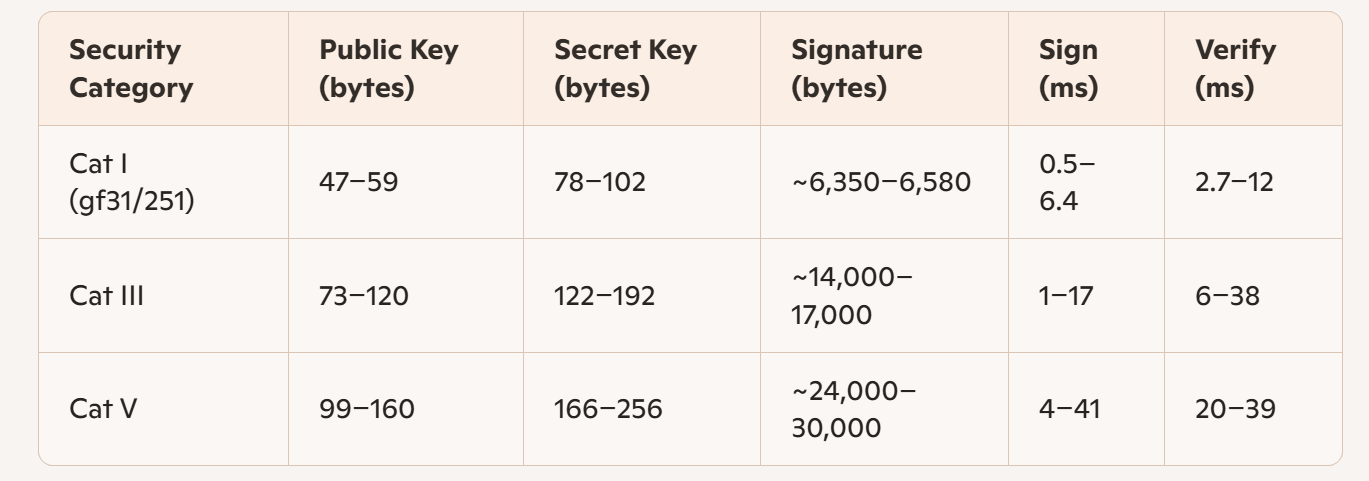

MQOM’s performance varies with parameter set but is generally as follows:

These times are for highly optimized AVX2 desktop implementations. Real-world embedded and non-vectorized scenarios can be slower. Signature and verification time is dominated by the usage of XOF (SHAKE-128/256) and hash functions, with substantial scope for hardware acceleration4.

MQOM’s public key size is among the smallest of PQ schemes, while signature size is moderate to large compared to lattice-based alternatives.

**Zero-knowledge proof-based batch proofs (e.g., zk-STARKs) have faster verification than zk-SNARKs but incur much higher proof size and computational cost for proof generation—a tradeoff made in favor of quantum safety and transparency (no trusted setup)11. Recent benchmarks indicate ZKPs for transaction validity on blockchains are still an order of magnitude larger than equivalent lattice-based ZKPs, though ongoing research continues to close this gap.

3.2 Lattice-Based Systems

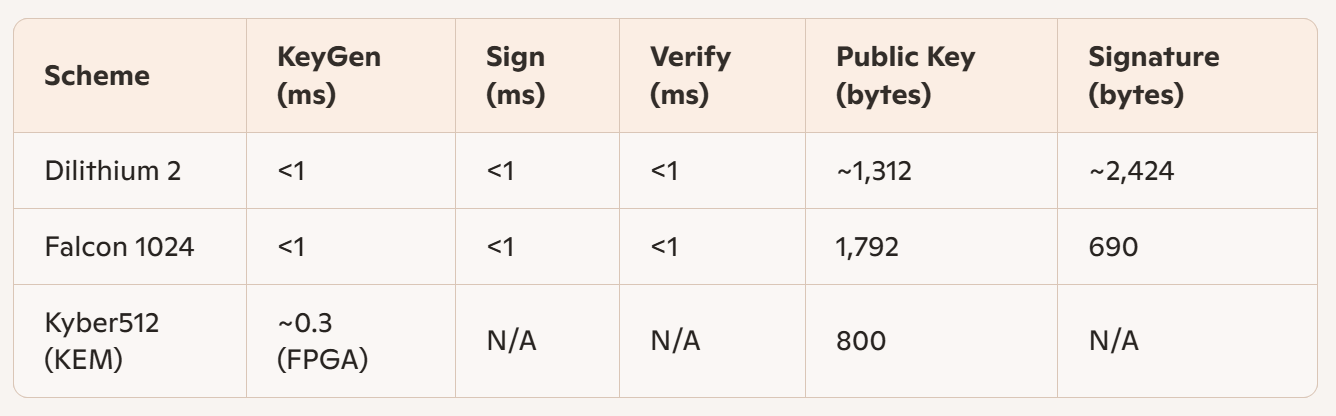

Lattice-based digital signature schemes demonstrate the following performance (based on current benchmarks on ARM Cortex microcontrollers, desktops, and FPGAs):

Lattice-based schemes, especially Falcon and Kyber, benefit from high optimization potential (AVX2, NTT), and are already in production use in OpenSSL, Google Chrome, and embedded systems. FPGA accelerations achieve over 80x speedup versus ARM Cortex M4, and floating-point units further speed up Falcon on Cortex M718.

Signature size is generally much lower than in MQOM/zero-knowledge systems. Falcon achieves sub-1KB signatures, Dilithium slightly larger. Public key sizes are higher than MQOM but lower than most code-based or hash-based alternatives.

4. Key and Signature Size Comparison

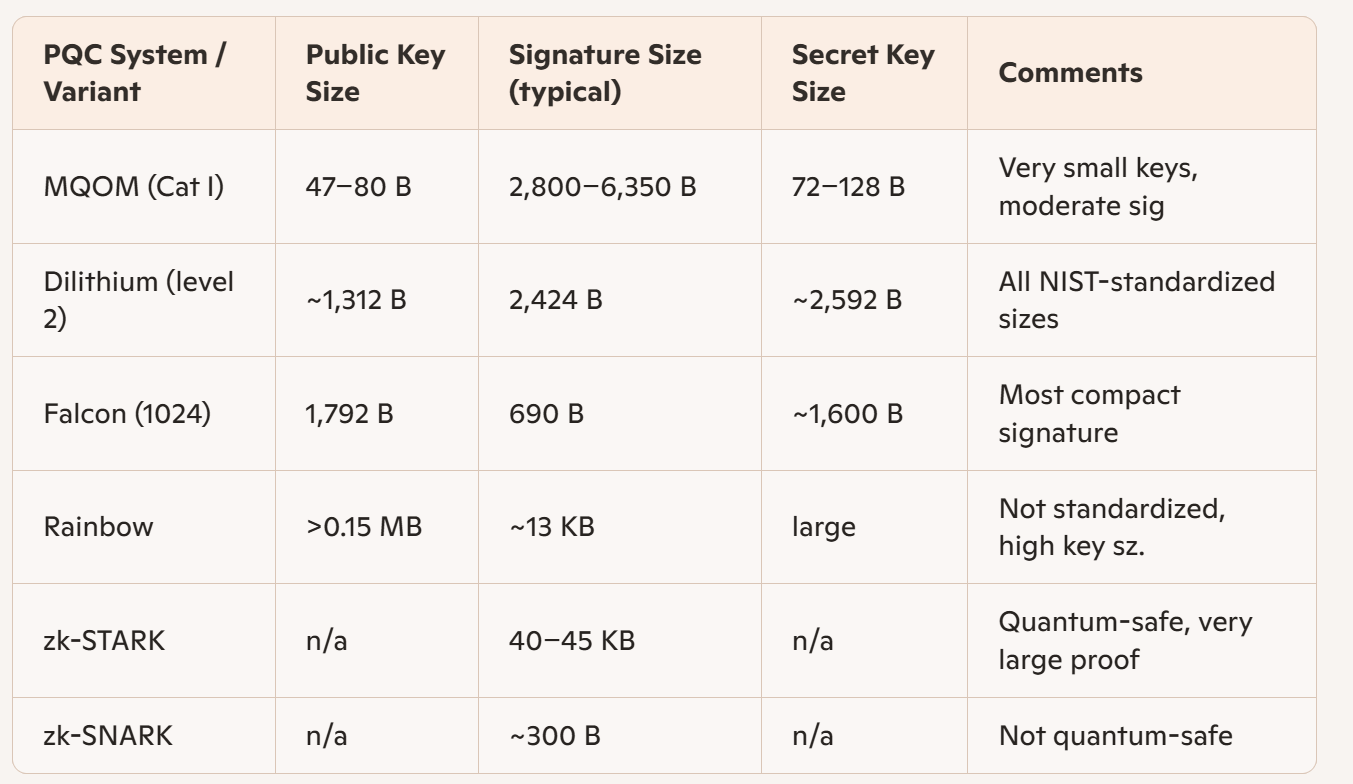

Key takeaways:

- MQOM offers extremely compact public keys and secret keys, which is attractive for resource-constrained authentication/authentication scenarios, and for protocols where public key transmission dominates cost.

- Lattice-based signatures (Falcon) dominate in minimal signature size, offering significant communication and storage benefits (e.g., for X.509 certificates, TLS handshakes).

- zk-STARKs offer the strongest post-quantum robustness but present debilitating proof/signature sizes, presently limiting their suitability to privacy-centric or bandwidth-insensitive protocols.

5. Computational and Implementation Complexity

5.1 MQOM and Zero-Knowledge Protocols

MQOM implementations are non-trivial and require:

- Polynomial interpolation (e.g., via Lagrange interpolation)

- Secure MPC simulation and seed tree generation (for commitment/reconstruction)

- Heavy XOF (SHAKE) and SHA-3 hash usage

- Serialization, masking, and random polynomial evaluation (for privacy and ZK soundness)

- Parallelization strategies (e.g., hypercube batching reduces N-party computation to log N + 1 parties)

This complexity is higher than most traditional signature schemes but offers inherent zero-knowledge and privacy-guarantees, making MQOM suitable for advanced authentication and confidential protocols.

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) using hash functions (as in zk-STARKs and MPCitH-based schemes) avoid the need for elliptic curves or pairings (which quantum computers can attack). Their complexity lies in managing large circuits, simulating honest parties, and compressing commitments without leaking witness information—all of which are actively researched areas with significant recent progress12.

5.2 Lattice-Based Systems

Lattice-based signatures and ZKPs depend on:

- Matrix-vector multiplications in high dimensions

- Number-Theoretic Transform (NTT) for fast polynomial arithmetic (critical for performance)

- Modular arithmetic for arithmetic in fields and rings (e.g., Zq[X]/(X^n + 1))

- Gaussian sampling algorithms, notably in Falcon, which complicate constant-time and side-channel safe software implementations (important for embedded and IoT)

- Optimizations for SIMD and vector instructions (AVX2, AVX512), harnessing hardware acceleration

Supported by mature libraries such as PQClean, liboqs, SUPERCOP, and now emerging lattice-based ZKP libraries like LaZer and Lantern, the implementation pathway is increasingly approachable even for non-experts19.

6. Application Suitability

6.1 Digital Signatures

MQOM / Zero-Knowledge Systems

- Suitable for signature applications needing zero-knowledge, privacy, or compact public keys. MQOM is resistant to chosen-message attacks (EUF-CMA) and features pre-computation for message-independent parts, supporting signing in intermittently-connected or latency-sensitive settings1.

- Notably, signature sizes can be too large for severely bandwidth-constrained systems, but their privacy and soundness make them attractive for high-stakes authentication and e-voting.

Lattice-Based Systems

- Best for high-volume signing and verification environments (TLS, email, cloud authentication). Lattice-based signatures meet both speed and size requirements, and their design is aligned with existing PKI system limitations (certificate field size, handshake speed, etc.)9.

- Falcon is particularly suitable for resource-constrained environments due to sub-1KB signature size. Dilithium offers implementation robustness and balance between computational load and size.

6.2 Authentication Protocols

- MQOM achieves excellent public key + signature size ratios, supporting privacy-preserving authentication protocols (e.g., ZK-based authentication, challenge-response schemes where user privacy is crucial).

- Lattice-based authentication and key exchange mechanisms (Kyber, NewHope, Saber) are being deployed in production systems, including PQ-TLS, where handshakes incur minimal latency and maintain high throughput. Falcon is already adopted in experimental TLS implementations, conforming to certificate size restrictions in PKI infrastructures.

6.3 Privacy-Preserving Protocols

- MQOM and zero-knowledge systems provide built-in zero-knowledge guarantees (N-1 privacy), making them well-suited for privacy-preserving, confidential applications (e.g., confidential blockchains, shielded transaction protocols, e-voting, whistleblower platforms)21.

- Lattice-based ZKPs (provided via LaZer, Lantern, MatRiCT) make possible advanced privacy primitives—anonymous credentials, group/ring signatures, verifiable encryption, and blockchain confidential transactions—with competitive sizes and efficiency. Recent hardening and performance enhancements are making their adoption increasingly practical21.

7. Implementation Libraries, Toolchains, and Hardware Support

7.1 MQOM and Zero-Knowledge Systems

- Reference C implementations and benchmarks for MQOM are available (GitHub), enabling reproducible performance evaluation and custom builds for embedded and high-performance use cases.

- Field sizes (gf2, gf256), and tradeoffs (short signature, fast timings) can be selected during compilation, with optimizations available for AES-NI, AVX2, and GFNI instruction sets. The code supports extensive precomputation to trade memory for computation time.

- Hash and XOF support: SHAKE128/256, SHA3-256/384/512, with SHAKE-acceleration a common area of hardware focus. Libraries for ZKP/OT based on hash and lattice primitives (LaZer, Lantern) are also available for research and prototyping in C and Python19.

7.2 Lattice-Based Libraries

- PQClean, liboqs, SUPERCOP—standardized and highly optimized C libraries supporting all major lattice signature and KEM schemes; compatible with OpenSSL and mbedTLS8.

- LaZer and Lantern: Research-grade libraries facilitating zero-knowledge proofs over lattices, with interfaces in C and Python, supporting applications from blind signatures to anonymous credentials13.

- Mature FPGA toolchains for Kyber, Dilithium, and Falcon, providing rapid performance acceleration for embedded environments and cloud HSMs.

8. Standardization and the NIST PQC Process

- Lattice-based schemes dominate the latest NIST PQC standards: ML-KEM (Kyber), ML-DSA (Dilithium), FN-DSA (Falcon) have been finalized in FIPS 203–2058.

- Multivariate and zero-knowledge proof-based schemes (e.g., MQOM, Picnic, Banquet) are under active review: The NIST call for additional signature schemes includes MQOM among the candidate submissions, though none have advanced beyond the round-one call as of August 2025420.

- Hybrid schemes deployed in the field: Several real-world systems deploy hybrid approaches (e.g., Dilithium + ed25519, or PQC + classical), especially for long-term cryptographic agility and risk mitigation during the transition period.

9. Cryptanalysis and Security Maturity

10. Case Studies and Advanced Applications

10.1 Blockchain Confidential Transactions

- MQOM and analogous ZKP-based schemes provide strong privacy for confidential transactions on blockchain, especially in settings where knowledge of a secret or balance must be proved without revealing it (RingCT protocols). They are commended for threshold privacy, message binding, and unforgeability. Challenges remain in reducing signature sizes to minimal viable levels for high-throughput blockchains24.

- Lattice-based ZKPs (e.g., MatRiCT, Lantern, LaZer) deliver efficient ring signatures, range proofs, and batched verification, with improvements in proof size and verification times enabling practical integration with blockchain systems (e.g., Hcash blockchain uses MatRiCT). Lattice ZKPs are now practical for large anonymity sets, facilitating Monero- and Zcash-like privacy but with quantum resilience22.

10.2 Hybrid Schemes

- Mixing MQOM signatures with lattice-based encryption/KEM is feasible and advisable in certain settings where layered defense is desired. Examples include hybrid PQC protocols with classical and post-quantum signatures, or mixed-use cases in IoT authentication, critical infrastructure, or government applications.

- Hybrid signature libraries (e.g., Dilithium/SPHINCS+ + ed25519 in one flow) are being developed for cryptographic agility and risk mitigation.

10.3 Hardware Acceleration and Embedded Implementations

- MQOM and ZKP-based schemes are not yet as hardware-optimized as lattice-based cryptography. Nonetheless, heavy reliance on SHAKE and SHA3 can benefit from ever-improving hardware hash accelerators—trend lines suggest much improved efficiency for embedded PQC signature generation/verifying in the near future, especially with ARM cryptographic extensions and custom ASICs3.

- Lattice-based schemes (Kyber, Falcon, Dilithium) already enjoy highly competitive FPGA designs, delivering sub-ms key exchange and signatures on ARM, FPGA, and cloud environments. Libraries like LaZer and Lantern (for lattice ZKPs) and support in OpenSSL 3.5 mark a new phase in ready-to-deploy PQ cryptography.

11. Parameterization and Future Trends

11.1 MQOM Parameter Trade-Offs

- Security levels scale with MQ field size, number of variables/equations, and number of parties in the MPC simulation. There is a quadratic signature size growth with the soundness parameter, tunable between "short" (smaller signature) and "fast" (faster signing, larger signature) variants. Seed tree and hypercube optimizations further reduce computation and communication cost1.

11.2 Lattice-Based PQC Trends

- Standardized parameters in NIST PQC schemes are likely to see refinements as further cryptanalysis matures. There is a shift toward more modular and efficient rings, better randomness extraction, and continual upgrades in implementations for hardware and software8.

- Lattice-based ZKPs are gaining ground, offering succinct proofs approaching the efficiency of classical SNARKs but with full quantum-safety14.

11.3 ZKP-Post Quantum Proofs

- zk-STARKs and lattice-based ZKPs are the leading approaches for future privacy-preserving protocols in quantum-safe regimes. Ongoing developments strive for lower proof sizes, faster verification, and full composability (SNARK-like in succinctness, STARK-like in transparency)17.

12. Educational and Research Resources

- MQOM:Official website and implementation repository23,NIST MQOM documentation.

- Lattice-Based Cryptography:PQClean,liboqs,LaZer Library,Lantern Tutorial13.

- Standardization and NIST PQC:NIST PQC project page;NIST IR 8545.

- ZKP Research:IBM Research ZKP Projects.

Conclusion

Both MQOM/zero-knowledge proof-based cryptography and lattice-based systems provide robust foundations for a post-quantum world. MQOM excels where small public keys and built-in privacy are paramount, at some cost in signature size and computational load; it is particularly suited for privacy-preserving, authentication, or bandwidth-flexible scenarios, and continues to improve rapidly in efficiency.

Lattice-based PQC is the gold standard in current digital signature and KEM deployment, offering an optimal blend of performance, compactness, and standardization. Libraries, hardware compatibility, and cryptanalysis maturity are significantly ahead, and ongoing work to bring ZK capabilities natively into lattice protocols is promising for the privacy needs of tomorrow.

Ultimately, the choice depends on use case specifics: for digital signatures with strict bandwidth constraints or embedded systems, lattice-based schemes such as Falcon or Dilithium are currently best-in-class; for strong privacy guarantees or novel zero-knowledge authentication, MQOM and related zero-knowledge schemes are highly suitable. Hybrid deployments and agility remain vital for long-term quantum resilience and cryptographic confidence.

References

1) https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/1719.pdf

2) https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/708.pdf

3) https://csrc.nist.gov/csrc/media/Projects/pqc-dig-sig/documents/round-1/spec-files/MQOM-spec-web.pdf

5) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lattice-based_cryptography

6)https://www.maths.ox.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/Overview%20of%20Lattice-Based%20Cryptography.pdf

8) https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography

11) https://markaicode.com/post-quantum-zk-rollups-starks-2025/

12)https://walletreviewer.com/zk-starks-vs-zk-snarks/

13)https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/457

14)https://research.ibm.com/projects/zero-knowledge-proofs

15)https://ascslab.org/papers/quantum-fpl19.pdf

17) https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/1846

18)https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/elex/17/17/17_17.20200234/_pdf

19) https://github.com/lazer-crypto/lazer

20) https://github.com/quantumcoinproject/hybrid-pqc/blob/main/README.md

22) https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/1287.pdf

23) https://github.com/FloydPing/mqom

24) https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-51280-4_25